By I.J. Baker

I’m not sure what makes me madder…the fact that I can find dozens of children’s books about the Vikings and the Tudors but only a couple about the partition of India, or that the books that do discuss Partition usually offer oversimplified and outdated historical narratives.

Why are there so few Partition books for primary-aged children?

A key reason is that Partition is not seen as part of British history or is thought of as only of interest to the South Asian community. It is erroneously depicted as something that happened so long ago and so far away that it is unconnected from our domestic life. This is unsurprising if you consider that the whole of the British Empire is left out of the National Curriculum.

The fact remains though that Partition is undoubtedly connected with life in Britain today. Recent census records show that in England and Wales people from Asian ethnic groups make up 9% of the population, making them the largest group after whites. These numbers can be traced back to Partition, which triggered the migration of formerly colonised South Asians into Britain (enabled by the British Nationality Act of 1948 which gave citizenship rights to members of the Commonwealth states.)*

The children’s authors that do bother to mention Partition frequently seem to model their narratives on W. H. Auden’s famous 1966 poem ‘Partition’: “two peoples fanatically at odds, With their different diets and incompatible gods… It’s too late, For mutual reconciliation or rational debate.”

The colonised people in Auden’s depiction, reduced to either fanatical Hindus or Muslims, are solely responsible for their misfortune. Meanwhile the reader sympathizes with the British rulers as represented by Cyril Radcliffe, a man beset by dysentery and living in fear of assassins as he tries to draw the new borders of India and Pakistan.

Some things have changed in the 60 years since Auden’s poem was published. You’d be hard pressed to find a recently published children’s book that is an outright celebration of the British Empire. And yet, the image of wise Britain trying to keep order over a violent mob endures, preserving Britain’s benevolent reputation.

The narrative follows a familiar pattern: The subcontinent is pacified and profitable under British rule, then all hell breaks loose when they leave. Britain ‘chose’ to quit India because it was too expensive to stay. The only resistance to colonial rule is the pacifism of Gandhi. The opinions and actions of the colonised people, their decades of strikes, protests, and boycotts which forced Britain to leave are never mentioned.

Fortunately, children’s books do have the potential to provide a more complex and honest narrative for young readers.

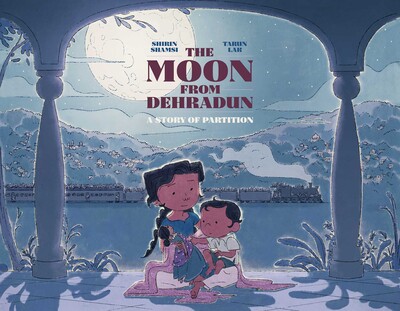

This can be seen in The Moon from Dehradun: A Story of Partition, a fictional story written by Shirin Shamsi and illustrated by Tarun Lak (Atheneum, 2022). This picturebook focuses on the intimate and emotional experiences of young Azra and her family and their fearful journey as refugees from Dehradun to Lahore. Shamsi focuses on the dire consequences of Partition on individuals swept up in overwhelming events beyond their personal control.

With distant fires burning across the skyline of Dehradun, the imagery relegates violence to the margins as one would expect for a book aimed at young children. The muted colours and somber expressions in Lak’s illustrations convey the seriousness of the story’s subject matter.

The Moon From Dehradun gives a voice to the experience of South Asians and defies the dominant narrative in Britain by erasing the supposed intractable differences between Hindu and Muslim communities. The words “Hindu” and “Muslim” do not appear in Azra’s story.

Azra’s family ‘trades’ homes with a Hindu family of refugees, and the visual similarities between the families’ clothes, furniture, and food enhances the readers identification of them as people with a shared culture and heritage. Religious objects such as a statue of Ganesh in the corner of the garden or the rolled-up prayer rug by a bookshelf could easily be overlooked and the reader must use context clues and other prior knowledge to recognise that the two families belong to different faiths.

This book is aimed at a readership of children between the ages of four and eight and by convention, must have a happy ending. However, Shamsi complicates the narrative by skillfully delving into the difficult history of Partition and the British Empire in the backmatter. This part of the text aligns with current scholarship that focuses more on political machinations than an inherent incompatibility of different religions. It challenges readers’ existing historical understandings by describing state-sanctioned violence of the British colonial administration and pointing to British “divide and conquer” policies as an underlying cause of Partition.

Shamsi demonstrates that even with a history as violent and fraught as Partition, it is possible to go beyond self-serving national narratives and write for children with nuance and complexity.

I.J. Baker is a PEG volunteer and public historian who is currently writing a young person’s guide to colonial history called “The Bloody British Empire.” Further writings can be found on their Substack page.

*For more on this topic I recommend Ian Sanjay Patel’s We’re Here Because You Were There: Immigration and the End of Empire, Verso, 2021.